I had a sales call last week that turned into one of those conversations where you realise the person on the other end is wrestling with the same question every HR leader eventually faces: How do you get people to actually use the thing you've built?

Raj (not his real name) runs an HRIS. It tracks goals three times a year. Mid-year reviews happen in October. Year-end evaluations close the loop. The system does everything it's supposed to do.

"Does it really help enhance performance?" I asked Raj."No, I don't think so."

This is the quiet reality behind most performance systems. They exist. People use them because they have to. But they don't actually change how work gets done.

The second lever most HR leaders forget

When you're trying to get managers and employees to engage with a new performance process, you essentially have two levers:

- Make it required. Set deadlines. Send reminders. Escalate to leadership when completion rates drop. This is the stick approach and it gets things done on paper.

- Make it useful. Design the process to solve a problem people actually feel. Build in moments that help them do their job better. This is the carrot approach and it gets things done in practice.

Most organisations default pulling the first lever (the stick approach) because it's faster to implement and easier to track completion rates which can be reported to leadership to show the system is being "used."

You can track completion rates. You can report adoption numbers to leadership. You can show the system is being "used."

But completion doesn't equal adoption. Just because a box is ticked, doesn't mean the system is making work easier, clearer, or more effective.

When the stick works (and when it doesn't)

During our conversation, Raj described two common performance problems: sales teams not hitting numbers, and teams struggling with behavioural issues between managers and team members.

For the first problem, mandating monthly target reviews might create accountability. For the second, forcing managers into a weekly 1:1 cadence merely creates the 'opportunity' for connection.

But these approaches won't necessarily addresses the actual friction people experience that is causing these performance problems.

I asked Raj what he thought was stopping his sales team from performing. He didn't know yet. That's the gap. You can't design an effective process until you understand the specific problem it needs to solve.

The alternative to forcing adoption

Instead of starting with "we need a performance system," start with the friction:

- Sales reps getting stuck on specific opportunities without guidance

- Employees unclear on which priorities matter most this week

- Managers unsure how to give feedback that actually helps

- Teams misaligned on what success looks like

When you design a process to solve one of these specific problems, you don't need to force people to use it. They use it because it helps them get unstuck.

One-on-ones can be incredibly valuable when they're designed to unlock specific friction. They're pointless when they're just another mandated meeting with no clear purpose.

The same applies to goal-setting, feedback processes, and performance reviews. The format matters far less than whether it addresses a real problem.

The accountability question

Raj raised something important during our conversation. He wanted to know how to hold people accountable when they're not following through on commitments.

This is where the stick versus carrot question gets interesting. If people aren't following through, you have two diagnostic questions to ask first:

- Do they understand what's expected? Often what looks like lack of accountability is actually lack of clarity. When I asked Raj to walk through his discovery process for understanding sales team friction, the conversation revealed he hadn't spoken to his sales team about what was blocking them yet.

- Is the process designed to create accountability or just track it? There's a difference between a system that records whether someone completed a task and a system that builds accountability into the workflow itself.

Raj's sales team has quarterly goals in the HRIS. They review them three times a year. But between those review points, what creates the rhythm of accountability? What prompts the conversation when someone gets stuck?

Real accountability doesn't come from annual reviews or completion dashboards. It comes from regular moments where progress gets discussed, blockers get identified, and support gets offered. That might be a weekly one-on-one with an agenda focused on top three opportunities. It might be a fortnightly check-in on specific skill development goals.

The structure creates the accountability. The mandate just creates compliance theatre.

Building accountability into the system

When we talked about his organisation's values and the struggle to get managers to consistently demonstrate them, Raj and I explored what accountability mechanisms could look like.

You can ask employees a single pulse question aligned to what you're trying to achieve. If one of your values is recognition, ask team members once a quarter:

"Have I been recognised for work I've achieved at least once this quarter?"

That data becomes reportable at the manager level. If an entire team says no, you now have evidence to start a conversation. Not an opinion. Not a complaint relayed through HR. Actual feedback from the team about whether their manager is executing the process.

From there, you can choose your level of accountability:

- Private conversation. HR discusses the feedback with the manager in a one-on-one. Lowest pressure, highest psychological safety for the manager to improve without public scrutiny.

- Public visibility. Share results across all managers so execution becomes visible to peers. Creates accountability through transparency.

- Career impact. Link consistent poor execution to promotion decisions or performance ratings. Managers who don't execute core processes don't progress.

- Remuneration impact. Build execution metrics into bonus structures or salary reviews.

Most organisations stop at private conversation or skip accountability entirely. But if a manager consistently fails to execute a process you've collectively defined as important, what does that tell their team about whether it actually matters?

Closing the loop on process effectiveness

The other critical piece I discussed with Raj was measuring whether a process actually achieves what you designed it to do.

Raj asked about onboarding specifically. They have a 60-day process for new employees. People go through it. Tasks get completed. But does it work?

I suggested defining the actual outcomes first. What should someone feel at the end of 60 days? Maybe they should feel clear on expectations, connected to their team, and confident about the next three months.

Then you ask them at day 60. Three simple questions. Rate how you feel on each dimension of clear, connected and confident.

If people consistently say they don't feel connected to their team, you haven't failed. You've learned something. You can orchestrate more touchpoints with team members in the workflow for the next cohort. Then you measure again.

This is the loop most HR processes miss. We launch the process. We track completion. We never ask if it delivered the outcome we designed it for.

Recognition programs that don't increase employees' sense of being valued. Development planning that doesn't increase employees' sense of career clarity. Review processes that don't increase employees' understanding of expectations.

We measure activity, but not impact.

What this means for you

If you're launching a new performance process and already planning your reminder emails and escalation strategy, pause.

Ask yourself: what specific friction are we solving for employees? What specific friction are we solving for managers?

If the answer is "we need better performance management," you don't have an answer yet.

The organisations with the highest adoption rates aren't the ones with the strictest deadlines. They're the ones where managers say "this actually helps me do my job" and employees say "I'm clearer on what's expected of me."

That clarity doesn't come from features. It comes from solving the right problem in the first place.

Want a deep-dive on your challenge?

Real world conversations like I had with Raj are a great source of inspiration for my writing.

If you'd like to jam with me on a performance management or PX topic - here's my calendar link. Lets chat and maybe I'll do a deep dive write up (de-identifed of course)!

The next time you'll hear from me will be in the New Year. I wish you happy, relaxing and above all, a safe holiday season.

Mark

CEO @ Crewmojo

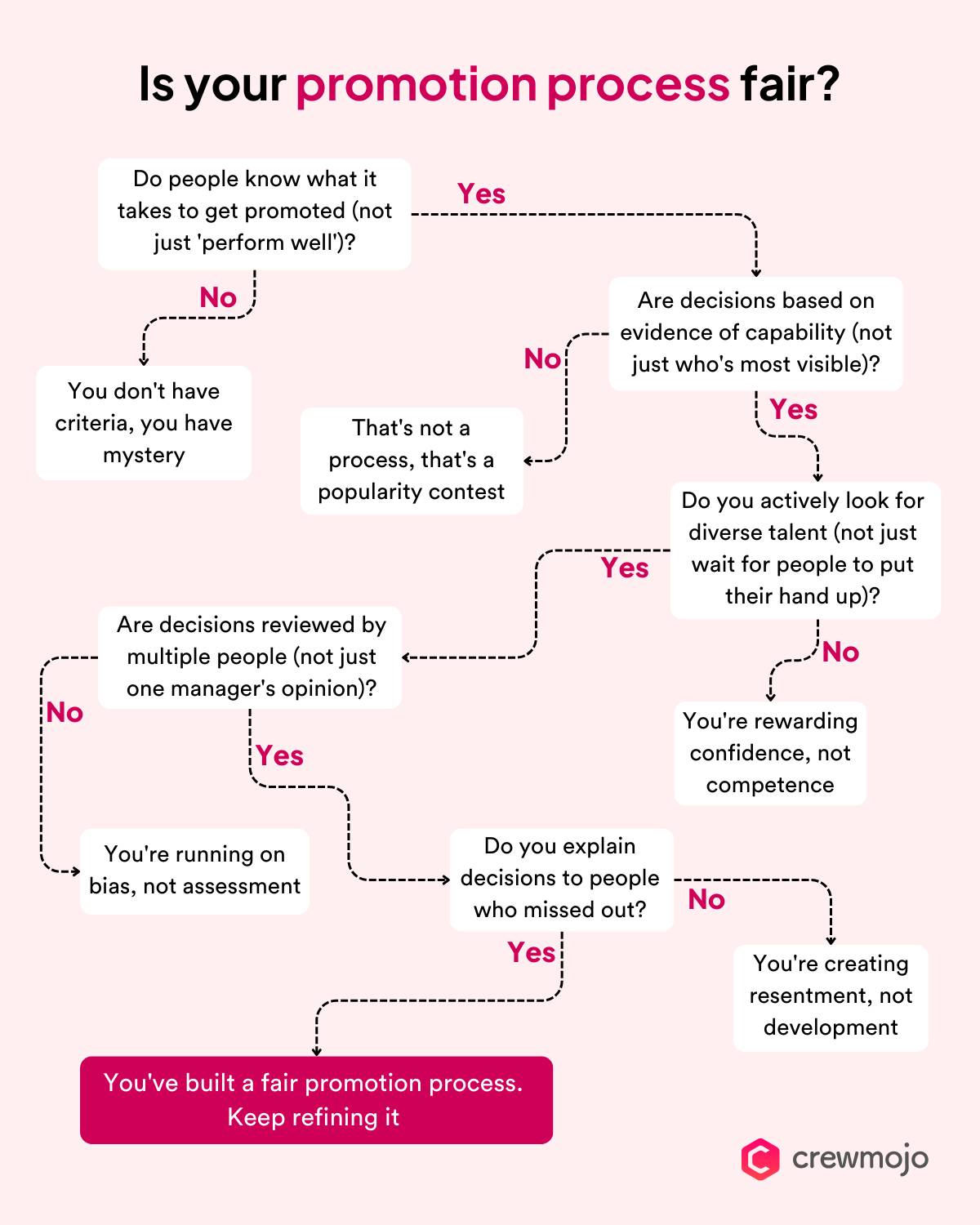

Most popular flowchart from this month...

Most organisations think their promotion process is fair.

Then they're confused when their best people leave or when the same types of people keep getting promoted.

We've seen this play out many times. The process feels fair to the people running it, but it doesn't land that way for everyone else.

The breakdown usually happens in predictable places:

👉 The criteria are vague or unwritten (so it's mystery, not a pathway)

👉 Or decisions favour the most visible people over the most capable

👉 Or they wait for people to nominate themselves (so confidence beats competence).

👉 Or it's one manager's call without broader input

👉 Or people who miss out get no real feedback (so they're left guessing or resentful).

Fair promotion processes are about being clear, evidence-based, proactive, calibrated, and transparent.

Subscribe to receive the latest posts to your inbox every month.